An Early Talent

Dare Wright’s mother Edith Pearl Stevenson (Edie) was born in Youngstown Ohio in 1883 to Samuel and Alice Gaither Stevenson. Samuel had come from his native England as a youth to work the iron mills of Ohio and nearby Ontario, Canada.

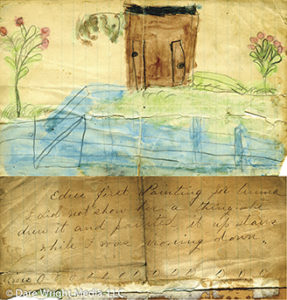

Edie’s artistic talents were in evidence early on. Her mother Alice saved Edie’s first painting on ruled paper with the notation, “Edie’s first painting…I did not show her a thing. She drew it and painted it upstairs while I was ironing down.” The picture is of a little hut standing on a grassy promontory surrounded by a stream. Edie’s mastery of perspective is still a few years away. What appears to be a cow, or perhaps a spotted dog, floats in the background.

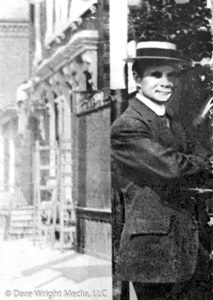

Edie would later tell an interviewer that, “From the time I was four I was drawing all sorts of things which people thought unusual for a little child.” She described how people’s faces had always had an almost hypnotic fascination for her. Once, as a little girl, her eyes became so fixed on the beautiful features of a young playmate that she collided with a tree and skinned her face. By the age of sixteen, Edie had become a paid artist. She worked under the tutelage of J.W.L. Forster at the Central Ontario School of The Arts, and later studied in New York at the Art Students League.

An Unusual Focus

Edie was lovely and petite. She possessed a mop of golden curls that other women might have tossed coquettishly to gather admirers. She did not, however, adhere to the Edwardian era’s concept of appropriate female behavior. Rather than lowering her large brown eyes demurely, Edie gazed straight into the soul of everyone she met.

Edie’s mother had scolded her for staring at people’s faces when she was a child. But what had seemed distressing in a small girl would prove to be an invaluable attribute for a portrait artist. A Cleveland magazine stated, “She looks people shrewdly between the eyes…and possess herself of what is essential in their mode of thought, and knowing this she has…the quick ability to transfer her impressions to the canvas while the inspiration is still vivid upon her.”

Edie was preparing to study abroad when Samuel Stevenson was fatally crushed as he was pulled into the machinery at the Hamilton Iron & Steel plant in Hamilton, Ontario. The December 24, 1903 headline in The Youngstown Daily Vindicator read: “KILLED: Samuel Stevenson Meets Violent Death — Deceased is survived by a widow, Alice Gaither Stevenson and three children, Alegeo, Edith and Fred.”

An American Artist

Europe would have to wait while Edie studied in New York. The art dealer William Schaus gave her a three-week exhibition in his Fifth Avenue gallery. It brought her enough orders to stay in New York for another two years. Looking back on the family tragedy years later, Edie put the best spin possible on her aborted European studies. In an article for the Cleveland News, she told Maude Truesdale, “It was a great disappointment not to go abroad, but perhaps it has not been a mistake after all. Mr. Schaus said that he thought a great many young artists were ruined by going abroad where they lost their individuality. He felt we should develop an American art, and learn to depict American manners and characteristics first.”

Acclaim Came Soon

By 1910, Edie had established herself as a successful artist in both Youngstown and the village of Thornhill outside Toronto, where her suitor Ivan Leonard Wright also lived.

A writer for The Toronto Globe effused with a surfeit of adjectives over both Edie and her work saying, “Here is the glorious optimism, the vibrating tenderness and the radiance that comes from the springtime of life alone, all softened by the mystic, ineffable prevision of sympathy; for the work is bathed in that glow of feeling and knowledge a working out in paint of intense emotional qualities never actually experienced in the artist herself, which, when all is said and done, we have to name by the old, old name that suggests, rather than defines, what the magic is. That there is magic in this slim girl you feel unmistakably if you sit, as did the writer, in the little Thornhill studio through long summer afternoons while a mysterious process of recreation went on.”

It was certainly Edie’s year. Her bread-and-butter portraits of charming moppets and their parents were in demand. She was also commissioned to paint the portraits of eleven of Ohio’s Mahoning County judges. They would hang in the new courthouse. She worked non-stop in her Thornhill studio, painting from photographs of the late justices. Then she moved to an improvised workspace of the fourth floor of the new courthouse in Youngstown to hold sittings for the living ones.

A Shattered Marriage

Edie completed the courthouse portraits before setting a wedding date with her dashing suitor, Ivan Wright. She then briefly put down her brushes to wed Ivan in Toronto on December 21, 1910. The Youngstown paper stated, “Miss Stevenson is an artist of recognized worth, and a girl of whom Youngstown people are proud.” More succinctly, it added, “Mr. Wright is a newspaper man.”

Ivan’s newspaper career ended when he lost his job at the Toronto Star. Edie’s painting commissions then supported the family as it grew to include first her brother Blaine and then Dare. By 1917, Ivan’s violence irretrievably shattered the marriage. He left for New York with five-year-old Blaine. Edie and Dare, who was not quite three, would make it on their own.

Edie and Dare’s Experiences As Adults

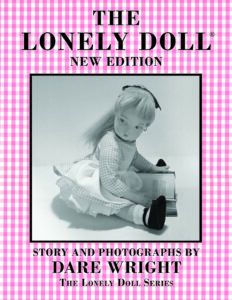

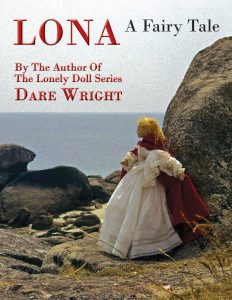

Soon after growing up in Ohio, Dare moved to New York City to pursue a career in acting, then fashion modeling. The move eventually led to the discovery of Dare’s talent with a camera, and to the creation of her now-famous children’s stories. Dare’s adventures and her relationships with her mother Edie and her friends and suiters are revealed as never before in Brook Ashley’s new biography, Dare Wright And The Lonely Doll. The book is richly illustrated with more than five hundred of Dare’s photos and other images.